From Soil Health Card to e-NAM: Work and Life of a Farmer

ARTICLES

Dr. Ankita Roy

11/8/20254 min read

India, the world's second-largest agricultural producer, is a leading global exporter of commodities such as rice, spices, and cotton. Agricultural exports are vital to the nation's economy, contributing 15-18% of the Gross Value Added (GVA) and reaching approximately $50 billion in Fiscal Year 2023. Beyond direct economic output, agriculture's most significant impact lies in job creation, providing livelihoods for over 45% of the total workforce across diverse roles and skill sets. The employment generated by this sector stimulates consumer spending and drives demand in other sectors, creating a ripple effect throughout the economy. Despite being a key economic driver for our nation, this sector is characterized by stagnant or slow income growth for the everyday Indian farmer. In 2018-19, a farmer earned approximately ₹10,240/ month, which was 2.5-3 times less than those in non-agricultural sectors.

Investigating the Income Disparity in Farmers

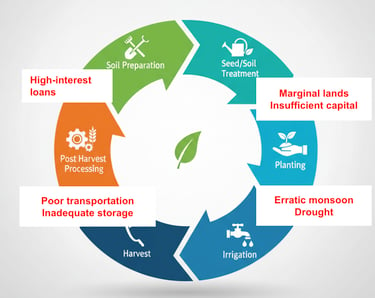

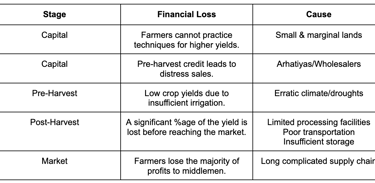

The stark income disparity necessitates addressing its underlying structural causes: fragmented landholdings, heightened climate vulnerability, and an inefficient and leaky post-harvest supply chain. Approximately 86% of farmers own marginal or small lands which hinders the ability to adopt modern practices, access credit, and profitably sell market produce. They are highly susceptible to erratic weather, resulting in crop failures and income losses due to inadequate irrigation and climate-vulnerable infrastructure. An inefficient post-harvest supply chain further exacerbates these losses through poor storage, transportation, and limited processing facilities. The farmer is trapped in cycles of debt and poverty, depriving him of his rightful share of the produce's value, while simultaneously leading to food wastage and higher consumer prices.

Farmer undertakes a crucial soil preparation process to break up compacted soil layers deeper than 40 cm using a traditional plough, a rotavator, or a chisel. Next, he refers to the government-provided Soil Health Card (SHC) which serves as a vital resource, offering guidance on how to effectively manage both nutrient levels and the pH balance of the soil. Soil Prep is followed by the labor-intensive process of fertilizer and pesticide application. He applies fungicides (Carbendazim) or bio-agents (Trichoderma spp.) via slurry or seed dressing to protect seedlings from soil pathogens.He then uses semi-mechanized Seed-cum-Fertilizer Drills for precise seed and fertilizer placement, replacing manual application. Micro irrigation, using drip and sprinkler systems (95% water use efficiency) and fertigation, addresses water management challenges in both rainfed and drought-prone areas, a significant improvement over flood irrigation. However, the farmer needs to monitor for pests and diseases and weeds leading to high operational costs and physical risks.

The farmer cultivates his crops until harvest. Post-harvest processing involves determining accurate physiological maturity (maximum dry matter accumulation) for minimizing post-harvest losses and ensuring optimal yield. Unfortunately, traditional harvesting, immediate transport, and poor handling significantly still contribute to significant post-harvest losses. After harvest, the farmer brings his produce for sale at the nearest ‘Mandi’ market. The selling process, typically an auction, involves licensed traders bidding on goods. Commission agents and other traders often facilitate sales between farmers and buyers.

National Agriculture Market - eNAM The mandi system (e-NAM), established under the Agricultural Produce Market Committee (APMC) Act, functions through a network of market yards under stringent regulations. While this system intends to assist farmers, they get a very small share of the final price. Middlemen (Arhatiyas) and wholesalers dominate transactions, offering farmers pre-harvest credit. This creates dependency, forcing farmers to sell exclusively to them, often resulting in lower prices and limited options. Farmers frequently engage in distress sales post-harvest due to urgent debt and limited financial access. Moreover, the supply chain is long and complicated adding to the problem. Poor storage and transport cause significant food waste leading to high marketing costs. Studies show farmers might only get 30-50% of what consumers pay for vegetables like tomatoes and cabbage, with the rest going to the middlemen.

The reward to risk ratio is pretty low for farmers.

Despite achieving record food grain production (3000 lakh metric tonnes) in 2023-24, reward to risk ratio remains pretty low. Significant capital expenditure on seeds, fertilizers, and pesticides, coupled with reliance on expensive credit, erratic monsoons, and increased market risk due to Mandi price volatility, leads to low profits for the farmer. Even with a good harvest, high marketing costs and low income often keep the farmers in debt. These problems, combined with social and economic issues, contribute to the well-known struggles in rural India. Integrating technology and digitalization can transform Indian agriculture, making farmers self-reliant entrepreneurs.

India's first one-stop all Digital Platform for Farmers

Digital tools reduce reliance on middlemen and increase their earning potential. Mobile platforms offer instant access to expert advice, weather forecasts, and market prices, eliminating dependencies on the unreliable traditional sources. This leads to reduced crop wastage, increased farming efficiency, and higher incomes through direct access to buyers and better price negotiation. Hopefully, informed decisions and easier market access can foster self-reliance in farmers thus, breaking many generations of debt cycles. Stay tuned for future updates on Sierra Blue’s one-stop all digital platform, designed to support Indian farmers and uplift agriculture.

Contact

Agentic Perception for Farms, Cities, and Secure Zones.

hello@sierrablue.in

© Sierra Blue Innovations 2025. All rights reserved. CIN: U62099MP2025PTC080355

Email: hello@sierrablue.in I Registered Office: House no. 106, Alpine Jewel 5CM4+P44, Mahabali Nagar, Kolar Rd, Bhopal, Madhya Pradesh - 462042